By David Dellenbaugh – https://www.speedandsmarts.com/

Strategy and Tactics – WEBinars Presented by Speed & Smarts

Dave will be leading three new webinars during the US winter and spring of 2024/2025. Each of these will include four live sessions geared toward a wide range of racing boats and sailors. For more info or to register click here.

Getting a Feel For Steering

The beauty of a hand on the helm is the control and the unmistakable power of feel. When it feels right, it feels fast.

Telltales are an excellent guide for steering in the groove upwind. You can shift gears within the groove by subtly varying the position of the windward telltales.

I had a chance to go iceboating for the first time a couple of months ago but I didn’t understand how anyone could sail without seeing wind on the water.

After two days of scooting around in Nites and Skeeters on Wisconsin’s Lake Geneva, I learned that “feel” is everything. The only way to tell how high or low you can steer is by feeling the wind pressure on the rig and the speed of the boat going over the ice.

It’s amazing how sensitive you become to these when you can’t rely on normal visual clues.

In many ways, steering a “water” boat is like steering an iceboat. It requires a sensitive touch. Steering is, by definition, the technique of guiding a boat from one point to another. It’s a fine art that requires practice, concentration, and the ability to experience a boat almost as an extension of yourself.

In order to go fast, you have to use a combination of rudder, weight and sail trim whenever you deviate from a straight line.

Steering Upwind

Steering a boat upwind has always been one of my favourite parts of sailing. One important thing is to sit (or stand) in a good place. Position yourself as high off the water, as far forward, and as far outboard as possible. This will give you the best view of your sails, the waves in front of your boat, and the rest of the racecourse.

Be sure you are comfortable, so you minimize distractions and maximize your attention span.

Once you’ve settled into a “batting stance,” you’re ready to start looking around and driving. To steer fast, you must assimilate information from several sources. Let’s discuss some of the guides you can use:

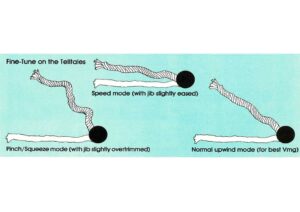

Jib telltales:

This is where I look most often when steering upwind. Like a lot of helmsmen, I probably depend too much on this single source of information. But telltales are a very good indication of how close I am sailing to the wind.

By watching the exact position of the windward telltales, I have a clear idea of whether I am slightly pinching, slightly footing, or sailing a normal upwind angle (see diagram).

Remember that easing or trimming the jib will affect the telltales; also, if you’re watching only the lower telltales, you may be misled if they are breaking differently from those at the top part of the sail.

The angle of heel:

A lot of good sailors steer by watching and feeling how much the boat heels. They find a heel angle that feels fast, then steer to maintain that angle (and the corresponding amount of weather helm).

The easiest way to keep track of the heel is by watching the angle that your forestay makes with the horizon. Using heel angle is actually another way to gauge how close you are sailing to the wind; the higher you head, the less you heel, and vice versa.

Instruments: Get a feel for steering

If your boat has instruments, one of your priorities should be to post target speeds for each wind velocity within easy sight of the helmsperson or tactician. These are helpful for knowing whether you should steer the boat faster or slower or lower or higher) at any given time.

Be sure to mount your boat speed readout (and other important instruments) on the mast or in a location where it is easy to read while looking forward. That way you can simultaneously watch the instruments, telltales, waves and angle of heel without looking away.

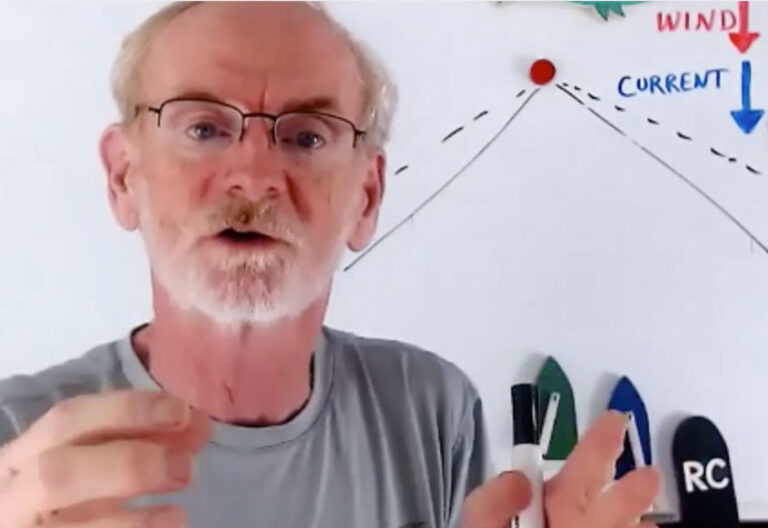

Look outside the boat:

It’s a good idea to make sure someone is always assigned to watch for puffs, lulls, waves and flat spots. Anticipating a change in conditions is key for steering. It lets you know whether you will have to head up for a puff or head off to punch through waves.

On small boats, the lookout is usually the skipper; on larger boats, it might be the tactician. Communication should include comments like, “There’s a puff coming in 20 seconds” or “Two steep waves in a boat length.”

Make sure these are loud enough for both the helmsperson and sail trimmers to hear.

Steering technique depends a good deal on how you’re moving relative to other boats. I like to have one crewmember (it could be the lookout) give me continuous readouts on our speed and height compared to our “neighbors.”

This helps me know whether I should steer higher or lower. If we’re having a problem, I’ll ask for feedback on what the other boat is doing. Often a slight change in my steering technique will make a difference.

Practice and experience:

Time in the boat is often the best way to learn how to steer fast.

The first time we sailed Heart of America in Fremantle, for example, Buddy Melges tried to steer the waves as if we were in a Soling.

Unfortunately, this didn’t work for a 12-metre. It took us at least a month of sailing every day to figure out how to get through those seas quickly.

Steering Downwind

Steering downwind seems easy at first. After all, you just head for the mark and trim your sails. But it’s not so simple if you want to go fast.

Finding a groove downwind is usually much harder than upwind. You don’t have the positive feel of weather helm, and it’s tough to settle in on a heading where the boat feels like it is effortlessly making its best VMG downwind. Fortunately, there are a few guides you can use.

Course to the mark:

The shortest distance between any two points is a straight line, so you can often steer straight for the next mark, and trim your sails to match. This is especially true on a reach.

I’ve used a point on shore, a compass heading, a light on shore, the stern light of a boat ahead, and even a star to help me steer a steady course.

Just be careful not to get so fixed on one heading that you ignore changes in the wind and other variables.

Polars and Target speeds:

These are just as important for steering on a run as they are on a beat.

What you need is a chart that gives your optimal wind angle and boatspeed for each true wind speed. When you find the angle your boat likes, set your pole position and steer up and down to maintain good pressure in the sail.

Spinnaker trimmer:

If you don’t have polars (and even if you do), one of the tricks to steering fast downwind is communication between the spinnaker trimmer and helmsperson.

When I’m steering on a run, I key almost entirely off the spinnaker. I look for changes in the shape of the chute, which indicate there has been a change in either wind direction or velocity.

I also listen carefully to my trimmer who continuously tells me what kind of pressure is on the sheet and whether we should head lower to burn speed or head up to build speed.

Feel: Get a feel for steering

Sensitivity is especially important downwind for several reasons.

First, the downwind groove is usually “mushy,” so it takes extra awareness to know when you are there.

Second, you can’t read the wind on the water as easily because you are facing away from the wind.

Third, the wind you feel (apparent wind) is less when you’re sailing down the wind, so it’s harder to feel on your body.

I usually try to sense changes in the breeze on my ears and the back of my neck. I’ve heard stories that Dennis Conner actually gets his hair cut before major regattas so he can feel the wind better.

This may not be necessary for most people, but it’s a good argument for not hiding your head under bulky clothing.

One final suggestion

Keep your rudder as still as possible when steering downwind. This is a change from going upwind, where the rudder actually provides lift and can help you wiggle around waves.

When you’re going downwind, however, the main result of rudder movement is increased turbulence and drag (except when steering to catch waves in surfing conditions), so use your weight and sails to neutralize the helm.