Insight into Running a Big Boat Program.

Brett: For something a little different from the normal sailboat racing tips I am speaking with Rod Hagebols, an extremely well-qualified professional sailor and accomplished sailing coach.

A few Classes that Rod has sailed:

Int Cadet, Fireball, Flying Dutchman, Int 14, Etchells, Star, J24, 12m, Soling, 1D35, Quarter Ton, Farr 40, Sydney 38, TP52, Maxi.

Rod’s Notable Sailing Achievements:

- Victorian & Australian Champion Fireball,

- Australian and Pre-Olympic Champion Flying Dutchman,

- South Pacific Champion Int 14,

- Coach James Spithill Youth Match Racing Worlds & National

- Coach – John Dane III and Austin Sperry – USA Star class representative Beijing Olympics 2006 – 2008

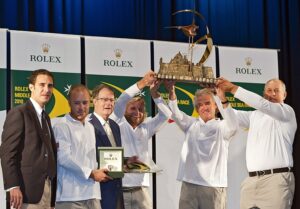

- Overall, Winner – 2010 Rolex Middle Sea Race – Lucky TP52

- Overall, Winner Line honours/ IRC – 2013 Audi Hong Kong to Vietnam – Lucky TP52

- Overall, Winner Line honours/ ORC – 2017 Palermo to Montecarlo – Lucky RP63

Rod’s going to enlighten us about what goes into campaigning a large boat on the international circuit.

FREE BOOK – TIPS and STRATEGIES

Brett: When we first met, you were heavily involved in dinghy sailing with a view to representing Australia in the Olympics. What was the impetus to get you into keelboat and offshore sailing?

I was lucky enough to do some sailing with David Gotze out of Brighton and did my first offshore race with David on the Sword of Orion or Brighton Star back then, which was a Reichel Pugh 43’ and we did the Melbourne – Hobart.

In my first offshore race, we broke the rudder just on the other side of Bass Straight, near King Island and unfortunately, we had to make up the emergency steering, which I can tell you wasn’t that flash but luckily the wind was blowing us straight back to the heads.

We spent 24 hours, me and another young guy, hanging onto the spinnaker pole out the back of the boat with the floorboards strapped to it.

So that was my first foray into offshore sailing. But it didn’t put me off. I guess from that point on, I learned about preparation and making sure your emergency procedures and everything are in place because I saw firsthand sort of what could happen if things go bad.

That started me off on the offshore program and big boats.

Obviously, I don’t think there was any real paid professional sailing going on back then. And actually, the size of Maxis back then, the big boats back in the 80s and ’90s, I think the big boats you’d call a 60-footer.

Well, it’s amazing how the boats have just got bigger and bigger and now we’re into the 100 footers.

Not too many professional sailing gigs back then. You just sort of did it for the love and still do. I didn’t really see it as a career path.

It was more just learning about sailing, and there were a lot of good guys and a lot of offshore sailing back then.

But I got into it I actually did that, as well as the One Design stuff and found it a very good marriage.

So that’s where it all started.

- And so I moved over to the USA back in 2000, and I lived over there for 15 years. And during that period, I did half a dozen Transpacs and Pacific Cups. Pacific Cup is San Francisco to Hawaii, and Transpac is from Los Angeles to Hawaii.

They were a lot of fun. I think I did three or four of those on a One Design 35, and we were four and five up. A great boat, a good downwind boat, designed by Nelson-Marek.

It was 10 days at sea going hard downwind, and so I learned a lot about downwind driving, and it was a lot of fun.

And during that period, I did some sailing on a Transpac 52. They were looking for a navigator, and I put my hand up to navigate for them.

The owner also had an Etchells, so I did the Etchells program and the TP52.

And that’s how my role as a program manager and tactician came about. My first tryout was our first Etchells regatta down in Miami.

We ended up third out of, I think it was like 90 boats.

I didn’t really know where it was headed at the time. Never would I have imagined that I’d be looking after a Maxi program.

Brett: So, you were the sailing master on the boat I believe.

Rod: Yes, a few of us are involved at different levels. There was a sailor who looked after the boat in terms of maintenance, and he delivered the boat to the venue.

That could be by ship or on its own bottom by water. His job was also to make sure all the equipment got to the venue and all the equipment was ready to go when the teams arrived.

Now in terms of the teams, at that level it becomes a lot of work in managing, let’s say, payroll. How all that works and the agreements you work out with the crew because everybody wants a different thing.

The simplest way for us was to work out a tiered system in terms of payroll because obviously, some people are more experienced than others.

In the old days, people used to work for food and board.

Well, that’s changed a lot since and there’s a lot of people with their hand out these days.

If we go to a venue where there’s a big regatta on, the logistics are not just payroll, but room and board and feeding the people. There is also the time when people need to arrive.

If you’ve got 22 people standing onshore twiddling their thumbs while the work is being carried out on the boat, it gets expensive.

You’ve got to make sure that as the team members arrive, the boat’s prepared in a way that either, you can have a full team there, the boat’s got to be ready to go sailing.

If it’s not, then it’s the partial team there who helps with the preparation over sails and so on and so forth.

So it’s sort of like a three-phase arrival pattern when we go to a venue, and that includes when the chefs arrive and when you’re cooking for 25 to 30 people. It’s usually at a regatta site.

FREE BOOK – TIPS and STRATEGIES

You won’t get a restaurant for that many people at a set time,

By far the cheapest and most time-efficient manner is to have chefs or a chef and a couple of sous-chefs who prepare lunches each day and have dinner ready, and lunches and breakfasts, if that’s necessary, depending on the venue.

But the most important part for us is the dinner at night when we come home, to make sure it’s ready and we can all have meals.

Usually, we’ll have one central house where the meals will happen and then usually there’s either a bus that goes around picking up crew, or sometimes there’s a couple of trips bringing crew in.

Quite often, if the house isn’t quite big enough, we will do two sittings with the meals, and you rotate that each day. There’s a lot of moving parts.

Brett: So gone are the days when everyone used to sleep on the boat or wherever they could end up. They’re long gone, I guess.

Rod: Sleeping on the deck is long gone. We certainly don’t rough it. We stay in some pretty nice housing, and we get well looked after. So that part of it has changed.

Brett: You mentioned that the boat can be configured differently rating-wise depending on conditions expected at a regatta venue.

Rod: Let’s say we’re going to go pick an event, basically, we look at what the goal is for the event, and we take a good look at what the venue is like, what the weather is like.

Then we start working with our navigators to work on a weather modelling and see what sort of winds and conditions we’re going to have.

So that then helps dictate what sort of sails we may work on for the event.

So we don’t throw endless dollars at a sail program. What we do is, rather than replacing a whole wardrobe, we’ll take a really good look at the sails that will be up most of the time and make sure those sails are in very good, if not new, shape.

And we try and look at that in terms of IRC rating.

And, you know, one of the biggest things I learned early on with the rating stuff is there’s no point, especially with IRC, there’s no point in carrying big sails if they’re not going to be up in the air. Just because you’ve got the big sail onboard means you’re getting penalized every second of that race that that sail is on board.

So if you’re going to take a big spinnaker, for example, you’ve got to make sure that it’s going to be up. Let’s say you’re doing the Sydney – Hobart and you’ve got a massive spinnaker. Well, you want to make sure the weather means you’re going to have a lot of downwind.

If you’re going to have three hours of downwind and you’re paying, 2 hours and 2 days and 20 hours of penalty, is that worth it? That’s the juggle you’ve got to do.

Brett: So, Rod, with your rating you have different certificates for different situations?

Rod: Yes.

Brett: How long out before the start of the race do you have to nominate which rating you’re using?

Rod: Usually in the notice of race, it stipulates when the last certificate can go in for the race. And that’s usually about a week to two weeks before the event starts.

Brett: So, you’re still taking a bit of a risk, aren’t you, with your plan?

Rod: A little bit of a risk. As an example, you know a Sydney – Hobart’s changeable, but a week out you sort of get a rough idea. So, you’re better off to have a close guess rather than no guess. And then if you’re not sure, you can always hedge either way a little bit.

But when you get races like Transpac, that’s not IRC. You go to Asia where you end up with weather patterns that are very trade wind-orientated.

FREE BOOK – TIPS and STRATEGIES

Brett: Okay. So planning is pretty important at the start of the regatta?

Rod: Well, yeah. When you consider, what the sail budget could be. Yeah. I have to look up what the spinnaker the value of a spinnaker is, but it’s not cheap.

Brett: How many events would you do a year?

Rod: I think the average over the period has been about three big events a year.

Brett: Okay, logistics are getting the boat there, whether it goes by ship or on its own bottom?

Rod: Yeah, that’s right. And so there’s a lot of planning that goes on with that.

Three 40-foot containers follow the boat around as well as a 40-foot chase boat.