Anticipation in Sailing Races – In every sailing race, to enhance your chance of success you must keep a constant watch ahead and around the course to see what’s coming and have a plan on how to deal with it before you get there.

Before You Leave The Beach

Before you leave the beach and before every race, you need to develop a plan to deal with the anticipated activity of the wind, waves, current, and other boats. Follow your game plan as closely as possible. Avoid spur-of-the-moment decisions that are made without regard for the big picture.

It’s hard to anticipate when you’re staring at the seaweed in the bilge. You have to keep your eyes looking up the course and all around for signs of things to come.

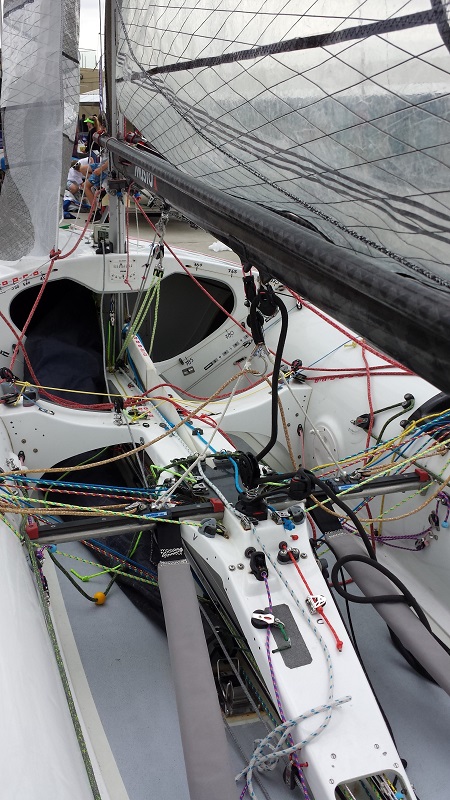

The helmsperson should concentrate on steering, so the crew really needs to be his eyes. Make sure one person on the boat has the responsibility for watching around the course and is watching for two things: changes in the wind or waves and the movement of other boats.

Crews Job

The crew watches for puffs, lulls, waves but to warn of approaching starboard tackers or boats on converging courses. To anticipate potential confrontations and to let the helmsman know of possible scenarios.

As an example the crew member who is assigned the task of looking up the course at the wind direction in relation to the marks needs to anticipate that when you come around the windward mark, will you want to do a normal bear away set, or a jibe-set and this needs to be communicated well ahead of time so you are set up at the mark to carry out that maneuver.

Communication

So that the helmsman can be informed about situations before they arise, they should call out in a voice loud enough to be heard by everyone aboard that there’s a puff coming, there is a crossing situation where you may need to duck or tack or the tactic needed at the next mark rounding and why.

In sailboat racing, things are always changing. It would be easy if we could plan ahead for every move on the race course but unfortunately, this is impossible because you can’t always predict what the wind will do or how the other boats are going to react.

What you can do is anticipate a number of possibilities that might happen. Then make a plan for each one.

By giving you time to consider decisions ahead of time, contingency plans help you stay in control of your race.